Perspective 3.0 - Linear Perspective

Vanishing Point (abbreviation: VP)

Imagine a road. Imagine there is a railway. We know that the lines of a railway lie parallel and will never actually meet. But, when we look far into the distance, we’ll see that as our gaze moves further, the two sides of the railway are going to come closer to each other. And then, far-far away, at the line of the horizon, it will seem as if they meet at one point.

The same thing will happen when you stare at a long-long road or a bridge.

You will seem to see, or at least you will be able to imagine, a dot where the lines meet.

This point is called a vanishing point. The parallels of your picture are going to meet in that point.

Let's take another example. Say, you take a cube.

Now, you place it on the ground, and you sit down to draw it.

That's how it will look from your point of view. And if you had Superman's X-ray vision, you could also see the inside:

Again, you know that each of the lines is parallel. But from your current position, some lines seem angled.

And if you take the four lines that seem angled, and if you continue them, they will cross at one point:

Like we said before, this is the vanishing point. In English, the notation "Vanishing Point" will be sometimes abbreviated as "VP".

And what's really cool in this particular case depicted below, is that if you "switch on" the background, you will see this:

The point where these (in reality) parallel lines meet, will be placed on the horizon line.

Remark: Please take into account that in the image above, the horizon line coincides with the true horizon (the boundary between the sky and the ground). However, they are not the same thing. As we've established before, the horizon line is the imaginary line that is right in front of your eye level.

Types of linear perspective

There are three types of linear perspective - one-point, two-point and three-point.

The drawing that we've just made is classified as the "One-point Linear Perspective".

One-point perspective

The main distinction of a one-point linear perspective is that it will have a single vanishing point, and it will be placed on the line of the horizon. All the parallel lines of your drawing are going to meet in that vanishing point.

It’s used in cases when the object is turned one specific side to us.

You will see the upper part of the object if the object is above your eye level. You will see the lower part of the object if it is below your eye level.

In some languages, the one-point perspective is called "frontal perspective" or "central perspective. I find that to be a fitting name since it helps to remember that you can's see the object's sides.

I will repeat.

You can't see the sides.

Many tutorials will teach you wrong assumptions about one-point perspective. When the artists don't have a solid understanding of perspective drawing, it's easy for them to make mistakes. But these mistakes will have devastating consequences on your art and the progress you make when drawing.

If you see someone saying that all of these cubes demonstrate one-point perspective, they are wrong:

The demonstration looks pretty, but it's not the correct depiction of a one-point perspective.

In a one-point perspective, the sidewalls of a cube will never be visible. So most of the cubes on the drawing do not represent the one-point perspective.

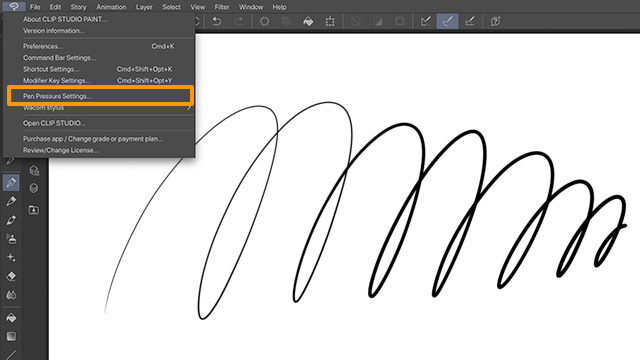

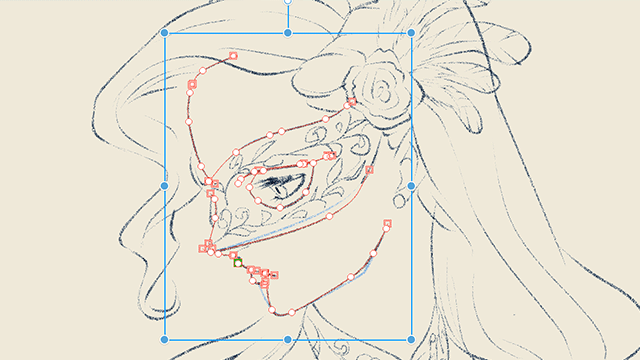

I'll redraw one of these cubes to show what I mean. I will use Clip Studio [Perspective ruler] to show you the guidelines and the vanishing points. Later on, I will also show you how to use the ruler by yourself, but first, you need to understand the one-point perspective.

Do you see this cube? Doesn't look too bad.

In fact, the cube itself is pretty correct. The vanishing point is placed correctly, and the horizon line is indicated. And yet, the drawing can be misguiding.

Because there is a second vanishing point that's not shown.

And this vanishing point is placed so far away, that it didn't fit on the canvas.

Because the distance between the two vanishing point is so big, it appears as if the two lines of the front face (the top line and the lowest line) are parallel. But they aren't. They cross in that second vanishing point.

I will move this vanishing point a bit closer to the first one, to demonstrate how the cube changes:

So, what you need to understand is that if the sidewalls of a cube are visible, it means that you're looking at an angle. And that's not a one-point perspective.

One-point perspective = "frontal" perspective.

I'm stressing this because I see pictures on the internet misrepresenting perspective. Perspective is complicated enough and doesn't need any further complications that will arise if you read a badly-written tutorial.

If you have a bad foundation, your house will be shaky. You want a nice, strong, properly-built house. Learn perspective properly. Solidify your art skills. Correct the mistakes early on.

Now let's move on.

Two-point perspective

The two-point perspective has two vanishing points. Both of them will be placed on the horizon line.

This linear perspective is used when you are facing the angle of an object. In a case when you're looking at a cube, you will see the sidewalls of the cub.

Another example of use: facing the corner of a room. This situation frequently happens in interior design.

----------In a one-point perspective, and in a two-point perspective, the vanishing points are placed on the horizon line.

That’s different from a three-point perspective.

Three-point perspective

A three-point perspective is similar to a two-point perspective, but it creates an impression that the viewer is positioned above or below the object. That is, you're looking up or down at the object.

As the name indicated, the three-point linear perspective has three vanishing points.

Two of them are placed on the horizon. The third vanishing point is placed either above the line of horizon or below the line of horizon.

When the vanishing point is placed in zenith (above horizon), then we’re looking up to see the object. We’re talking about the worm’s eye view, since we are in a position of a worm that’s looking up to zenith.

When the vanishing point is placed in nadir (below horizon), then we’re looking down. This is called the bird's eye view .

Remarks (will be discussed in the future):

---------------

Summary:

-----------Pretty simple so far, so why do artists make the mistake of misclassifying perspectives?

Why do artists misunderstand?

Originally, this and similar depictions were meant to serve as an exercise, to train your spatial awareness. In handbooks for artists, you will see small sketches added here and there, and some will seem to indicate only one vanishing point.

But that's because the other vanishing points were so far away, they simply wouldn't fit on the page! Or, they would make one small drawing of a cube, take up the entire page.

See the drawing below. It's a small sketch, but it takes up a lot of space.

To understand this sketch, you don't really need that third vanishing point on the right. The key vanishing point is the one on the left.

So, the "unnecessary" vanishing points are often omitted.

This is especially the case when you read the advanced parts of the handbook. The author assumes that you now understood the basic concepts of perspective. Therefore, the author does not draw everything and does not remind you of the existence of every single vanishing point.

In turn, this may cause some readers, who skim over the page and don't take the time to read everything, to misunderstand.

When you place the second vanishing point far away from the first one, the lines will seem parallel. They're not, but the difference is hardly visible from the first glance (and you saw this earlier when we redrew that blue cube).

All this leads some artists to assume that the handbook's author is talking about a one-point perspective since only one point is evident. The artists who have misunderstood the sketch would then draw incorrect cubes. They're practicing, so no harm's done to make a mistake, especially when this mistake is not obvious. The true problem arises when these artists start teaching others. They use the same pictures from the handbooks, redraw or copy them, and pass them along with incorrect explanations.

Now, if you look, the internet is filled with images of two-point and three-point perspective sketches labeled as one-point perspective.

Now the next generation of artists is looking up "simple perspective" tutorials or demonstrations and that's what they see.

They have never read the handbooks, so they can't tell the original intent of the exercise. They see that the sketch seems correct, so they trust the explanations. The new artists have no idea that the annotations are wrong. Trying to learn perspective, they copy the mistakes. And these very same mistakes are what makes you confused!

Take the time to learn perspective. Do not jump on the first occasion to "simplify" it. You will only end up getting more confused.

In the next episode, we'll see practical applications of linear perspective, along with some worthwhile tips.

Comment